PUBLISHED AT ADORAMUS.ORG

In an attempt to contain the spread of COVID-19, government leaders in the United States made the historically unprecedented decision to shut down all non-essential services. Religious services were deemed non-essential. As a result, something quite extraordinary happened. The baptized faithful found themselves unable to worship together liturgically in a church on Sundays. The timing of the decision in A.D. 2020 was all the more tragic and heart wrenching. It occurred during the most holy seasons of Lent, Holy Week, and Easter.

In an attempt to contain the spread of COVID-19, government leaders in the United States made the historically unprecedented decision to shut down all non-essential services. Religious services were deemed non-essential. As a result, something quite extraordinary happened. The baptized faithful found themselves unable to worship together liturgically in a church on Sundays. The timing of the decision in A.D. 2020 was all the more tragic and heart wrenching. It occurred during the most holy seasons of Lent, Holy Week, and Easter.

An already precipitous decline in Sunday Mass attendance, coupled with government ordinances that either forbid or severely curtailed the faithful’s ability to assemble on Sundays are serious matters for Catholics to consider—both now and in the future. To help understand the full gravity of the situation, it is important to consider the origin and meaning of the Lord’s Day, especially in relationship to the Eucharistic sacrifice and presence of Christ. More so, the Sunday Eucharistic liturgy sets the seasons and themes in which the full course of daily liturgies and personal prayers are celebrated.

Several well-meaning but inadequate responses to the pandemic-related curtailment of Sunday liturgies have been implemented. These include parking lot Masses, during which the people remained in their automobiles, and drive-up Communion processions. Also misguided is the tendency of the laity and even some clergy to be more anxious about reception of Holy Communion on Sunday than on how to “keep Sunday holy.” Such actions and responses demonstrate a crisis of faith rooted in large part in ignorance about the meaning and significance of Sunday—the Day of the Lord—and the full scope of the Eucharistic celebration.

A crisis, nonetheless, is neither cause for panic nor discouragement, but rather a call for renewed and deeper reflection. Carpe Diem (seize the day—especially the Lord’s Day)! These times that try the soul are ripe for evangelization. Hence, we might turn our attention to a poignant Apostolic Letter written by St. John Paul II in 1998 entitled Dies Domini—The Day of the Lord.[1]

The purpose of the present entry is to identify the key points in the Apostolic Letter that explain the meaning of the Lord’s Day and the purpose of its observance and celebration.

Begin Here

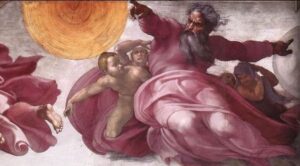

As with all things Catholic and Apostolic, one must go back to the beginning. Such is the place that Pope John Paul II began his Apostolic Letter. Reading carefully chapters 1 and 2 of the Genesis account, God both worked and rested. For six days he created, but then on the seventh day he rested—in Hebrew, Shabbat, thus the word Sabbath. God’s resting, however, is not inactivity but, rather, “a gaze full of joyous delight…, a ‘contemplative’ gaze which does not look to new accomplishments but enjoys the beauty of what has already been achieved” (Dies Domini (DD), 11). That divine gaze of joy fell especially upon the human person, made in the image and likeness of God. In the human person, God takes a greater delight than the rest of creation. In turn, the human person, created in the image and likeness of God, is called and invited to return the gaze of joy and delight in the Creator.

According to Genesis, the day of rest—the Shabbat—is the day blessed and hallowed (Genesis 2:3). Indeed, it is rightly identified as “His day par excellence” (DD, 14).It is the day set apart and therefore looks different than any other day of the week. First and foremost, according to the biblical tradition and upheld by an unbroken apostolic, Christian tradition, the day of rest is designated by God in order to refer all reality—space and time—back to God, who is the Author, Source, and Sustainer of all creation (DD, 14). It is the day also set apart specifically to renew and to strengthen one’s covenant relationship with God through dialogue. Such a dialogue demands specific times of prayer, when men and women “raise their song to God and become the voice of all creation” (DD, 15). The human person is created to participate in a priestly and kingly stewardship of creation. In Exodus 29, God established an ordained priesthood that is fulfilled centuries later in the divine Son becoming man and in his ordaining the Apostles at the Last Supper to his own priestly office. Thus, Christ’s ordained priesthood becomes the “voice of all creation” by honoring God through prescribed prayers and rites. Christians are called upon to participate in this voice by joining these “public” liturgical rites through speech, silence and presence.

Biblical rest, therefore, has a far more profound meaning than mere inactivity or an opportunity for entertainment. The purpose of the rest is to detach in order to renew. To rest from one’s routine rhythm of oppressive work expresses or manifests a fundamental truth. The cosmos and one’s personal life depend on God rather than the human person. The Sabbath rest makes a radical declaration: Everything belongs to God—the entire universe and its history.

Exodus and Mass

For the human person, the commandment to keep the Sabbath is not imparted until Exodus 20: “Remember the Sabbath day in order to keep it holy” (20:8). People have incorrectly attributed the commandment to rest on the Sabbath with Church law or civil law. It is first a Divine Law. In obedience to God’s command, ecclesial and civil laws were implemented in Christian governed societies. At one time non-essential work such as commercial transactions did not occur on the day of rest under penalty of law.

Sacred Scripture gives the reason for the commandment to keep holy the Sabbath: “For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy” (Exodus 20:11). Later, in the book of Deuteronomy, God’s word will further explain the reason for the decreed rest on the Sabbath, in addition to following God’s own example: “You shall remember that you were a servant in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm; therefore the Lord your God commanded to keep the sabbath day” (Deuteronomy 5:15). Both passages present the two reasons for the divine precepts: worship and salvation. The human person is commanded to rest not simply because God rested, but because God continues to act in the created world to give us access to his presence in the Eucharist and by means of this and other sacraments to eternal salvation in which we enjoy his presence forever.

The divine precept to rest has nothing to do with inactivity and entertainment and everything to do with worship of the God who offers us salvation. The day of rest requires an interruption from work, in order that: 1) the human person, the domestic church, and the Body of Christ dialogue with God in a manner filled with celebratory praise and thanksgiving; 2) the Faithful participate liturgically in the mighty deeds of God: the work of creation and the liberation from servitude.

A New Day for Mankind

In the New Testament, the work of Christ, accomplished by his suffering, death and resurrection, and the work of the Holy Spirit, begun on the day of Pentecost, continuing until the Second Coming, have wrought a new creation (a re-creation) and the liberation from the servitude to sin and death. These mighty deeds of God surpass the first work of creation and the first work of liberation. The new exodus, indeed, “was into the freedom of God’s children who can cry out with Christ, ‘Abba, Father’” (DD, 18). For these reasons, a fundamental shift occurred: the day of worship and salvation shifted to Sunday, for it was on Sunday that the Lord rose from the dead and the Holy Spirit descended upon the Apostles. Hence another name for the day of rest is Dies Christi—the Day of Christ, which is the title of the second chapter of John Paul II’s Apostolic Letter.

Chapter One of the Apostolic Letter offers an initial conclusion on how to worship in the midst of a pandemic: While one may or may not be sheltering-in or quarantining due to COVID-19, the Divine mandate to keep holy the Sabbath remains effective. The baptized are still expected to refrain from non-essential work and banal entertainment. This allows them 1) to detach and dialogue, 2) to detach and worship, 3) to detach and celebrate the mighty deeds of God.

Meet Christ Today

For any baptized person with a lived-faith, Sunday is an absolutely extraordinary day. Grasping the extraordinariness of Sunday, the first Christians, under the leadership of the Apostles, began to assemble on Sundays in order to remember and celebrate several key Christian events. First, Sunday was the day of the resurrection; second, Sunday was the Day of Pentecost, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit; third, Sunday was the day of the first proclamation resulting in the first baptisms; fourth, Sunday was the epiphany of the Church whereby a scatted humanity would be brought into unity. These biblical events are the very source of the world’s salvation (DD, 19). Thus, the baptized faithful began to meet on the “first day of the week,” Sunday. Nevertheless, law did not coerce them, but love impelled them.

In the first creation, God began to create on a Sunday when He said, “let there be light” (Genesis 1:3). The new creation—the re-creation—also occurred on a Sunday when the eternal light shown forth from the tomb and all things began to be made new in the resurrected Christ: “Behold I make all things new” (Revelation 21:5). Grasping the relationship of the Old Testament and New Testament regarding the first day of the week, the early Christians identified Sunday as the “day above all other days.” It “summons Christians to remember the salvation which was given to them in baptism and which has made them new in Christ” (DD, 25).

To conclude chapter two of his apostolic letter, John Paul II identifies three characteristics of Sunday: it is the Day of Christ-Light, the Day of the Gift of the Holy Spirit, and the Day of Faith.

First, Christ’s Divine Light, revealed at the resurrection, illuminates all things; his light scatters all darkness and the shadow of death (Luke 1:78-79); his light gives life. In short, Christ’s Light gives meaning and purpose to the other six days of the week. When the faithful interrupt their ordinary work, it is to enable them to praise, worship and adore the Light of the world. Similar to St. Simeon at the event of the Presentation in the Temple, each Sunday the Church with joy proclaims that Jesus of Nazareth is the light that enlightens the Gentiles (Luke 2:32). May that Divine Truth give the person with a lived-faith consolation and peace in the midst of a world darkened by pandemic.

Second, while Pentecost happened on a particular day in salvation history, nevertheless, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit is celebrated and recalled each Sunday. Pentecost was not only the “founding event of the Church, but is also the mystery which forever gives life to the Church” (DD, 28). For the faithful, therefore, similar to Easter—the event of the Resurrection—Pentecost is not merely an annual celebration but a weekly celebration. Each Sunday the Church re-lives and experiences anew an encounter not only with the Risen Lord but also the Life-giving Spirit. In the midst of the pandemic, may the one with a lived-faith take confidence that the Holy Spirit renews the face of the earth (Ps 140:30).

Finally, Sunday is the Day of Faith. The Holy Father offers the meditation that each Sunday, the liturgical assembly stands with St. Thomas the Apostle to: “Put your finger here, and see my hands. Put out your hand and place it in my side. Doubt no longer” (John 20:27). For that reason, each Sunday, the liturgical assembly stands and renews its own baptismal faith by reciting the Creed. It happens between the act of hearing the Word proclaimed and the act of receiving the Word in the Eucharist. Hearing gives faith (Romans 10:17), and faith must precede sacrament. Even in the midst of a pandemic, the gift of Faith conquers (1 John 5:4).

Sunday’s Essential Service

Human civilization has faced many pandemics far worse than COVID-19. Christendom itself has faced several horrendous pandemics—for example, the Black Death plague that afflicted and killed a countless number of people during the 14th century.[2] Nonetheless, never did the bishops or Christian monarchies en masse deprive the faithful access to the liturgy and sacraments. Recorded history reports the opposite occurred, the faithful’s liturgical and sacramental participation increased. It ought to be noted, as well, that even in times of persecution and threats of martyrdom, faithful bishops and priests made every effort to ensure the faithful had access to the sacraments and liturgy. Living in a secular and de-Christianized society, we are governed by political leaders and bureaucrats with little or no Christian faith, who have deemed religious services non-essential, while casinos, marijuana dispensaries, liquor stores, strip clubs, and other businesses are deemed “essential.”[3]

Where churches have re-opened, albeit with limited capacity, the faithful have another challenge: flexibility, commitment, and fortitude. Where permitted, parishes have taken great strides to make it possible to attend Sunday liturgy safely: limiting the size of the liturgical assembly, increasing the number of Mass times, enforcing safety precautions, and cleaning more regularly and thoroughly the churches.

Pandemic or not, for several foundational biblical and apostolic reasons, let us not forget that Sunday is an indispensable day. If one is going to work, going to school, going grocery shopping, going out to eat—where does Sunday rank, if at all? Indeed, take the necessary precautions but understand that Sunday is indispensable. Should health reasons prevent one from attending Sunday Liturgy, each household should make the greatest efforts to celebrate the Lord’s Day, not as a day set aside for inactivity and entertainment, but as a day for more serious times of prayer—dialogue with God (more on this in Part II). For the moment, however, let that prayer include the reading of the Scriptures, lighting a candle to remind one that Christ is the Light of the world, including a special prayer to the Holy Spirit asking that he renew the face of the earth and enlighten those entrusted with the responsibility to govern, and finally, reciting the Creed. Such ordinary recommendations can serve the faithful well in meeting our current extraordinary situation.

This article is part one of a two-part series by Father Mallick.

[1] John Paul II, Dies Domini, Daughters of St. Paul (Boston: MA: Pauline Books & Media, 1998).

[2] To date the Black Death remains the worst pandemic in recorded human history, wiping out up to 50%-60% of the population in Europe alone. The population of Europe is estimated to have been around 80 million. Upwards of 50 million died due to the Black Death. Today’s population in Europe is approximately 750 million. If 50% percent were to die from COVID-19 in similar fashion to the Black Death, then the death toll would be 375 million persons. As of November 29, 2020, the death toll is recorded at 396,865.

[3] “Coronavirus: Churches are essential. If protesters can assemble, so should people of faith,” USA Today; “Casinos Open, Churches Closed,” Outside the Beltway.

Father Marcus Mallick, born a Melkite in Fort Worth, Texas, was ordained a Priest of the Archdiocese of Denver, CO, in 2005, where he served three years as a parochial vicar and seven years as pastor of a parish. Father Mallick was granted an educational leave in order to pursue a Master of Arts degree in Liturgical Studies at the Liturgical Institute in Mundelein, IL. He also began researching his Melkite roots and came to petition for entrance into the Melkite Eparchy of Newton, where he has been accepted for five years ad experimentum as a priest in good standing.